Happy Persian New Year!

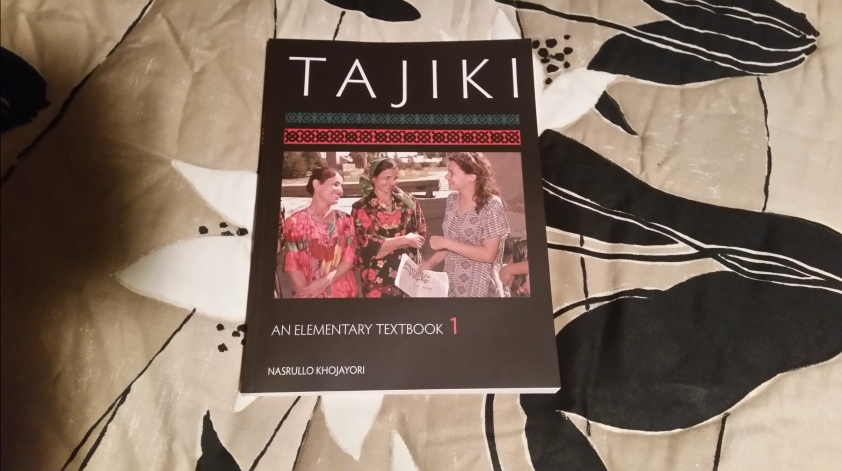

The most money I’ve ever spent on a language learning book. Came with a CD. Can’t imagine there are too many books that can say that about themselves in 2017.

In Late 2016 and Early 2017 I thought it would be becoming of me to try to learn a language of a Muslim-majority country for the first time. Yes, I did get the Turkish trophy in Duolingo but I don’t count that because the amount of Turkish phrases I can say as of the time of writing can be counted on my fingers.

The same way that the Catholic world is very varied (you have Brazilians and Hungarians and Mexicans and too many nations in Sub-Saharan Africa to list), the Muslim world is just as equally varied with numerous flavors and internal conflicts that Hollywood and American pop culture not only doesn’t show very often but actively tries to hide (or so I feel).

While I am not fluent (nor do I even count myself as proficient) in Tajik, I am grateful for the fact that I can experience tidbits of this culture while being very far away from it, and it seems oddly familiar to me for reasons I can’t quite explain.

What’s more, Tajik is one of three Persian languages (the others being Farsi in Iran and Dari in Afghanistan), and so I can converse with speakers of all three with what little I have. I remember being shocked about how close Swedish, Norwegian and Danish were to each other (to those unaware: even closer than Spanish, Catalan and Italian), and I was even more shocked at how close these were. The three Persian languages are even closer—so close that there are those (both on the Internet and in my friend group) that consider them dialects of a single language (yes, I’ve had the same discussion with the Melanesian Creole languages!)

As a Jewish person myself (and an Ashkenazi Jew at that, for those unaware that means that my Jewish roots are traced to Central-Eastern Europe), I was intrigued by Tajik in particular as the language of the Bukharan Jewish community.

(Note: Bukhara is in contemporary Uzbekistan, and if you see where Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan meet on a map and you have a hunch that imperialist meddling may have been responsible for those borders, then you’re absolutely right!)

What’s more, my father visited Iran and Afghanistan earlier in his life but when he was there the USSR was “still a thing”.

I also had a fascination with Central Asia as a teenager ever since I heard the words “Kazakhstan”, “Uzbekistan”, “Tajikistan”, etc. (despite the fact that I literally knew NOTHING about these places aside from their names, locations on a map, and capitals), and so between Persian languages I knew which one I would try first.

It has been hard, though! With Tajik I’ve noticed that there is a gap in online resources—a lot of stuff for beginners and for native speakers (e.g. online movies) and virtually NOTHING in between (save for the Transparent Language course that I’m working on).

Thankfully knowing that I have surmounted similar obstacles with other languages (e.g. with Solomon Islands Pijin) fills me with determination.

I’m sorry. No more “Undertale” jokes for a while.

Anyhow, what make Tajik unique?

- Tajik is Sovietized

The obvious difference between the other Persian languages and Tajik is the fact that Tajik is written in the Cyrillic alphabet, and much like Hebrew or Finnish, is pronounced the way that it is written with almost mathematical precision (despite some difficult-to-intuit shenanigans with syllable stress).

Thanks to not using the Arabic alphabet this obviously does make it a lot easier for speakers who may not be familiar with it.

Yes, in a lot of the countries in Central Asia (especially in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) there are some issues with what alphabet is used (and if you think that this has to do with dictators forcing or adopting certain systems, you’d be right!). Tajik I’ve noted is very consistent in usage of the Cyrillic alphabet, although obviously presences of the other two Persian languages e.g. on comment boards are present almost always whenever Tajik is.

But what exactly does “sovietization” entail? Well there are a lot of words that come from Russian in Tajik, and ones that were probably adopted because of administrative purposes. The words for an accident ( “avariya”) and toilet (“unitaz”), for example, are Russian loan words.

But unlike the Arabic / Turkic words in Tajik, a lot of these loan words refer specially to objects and things related to administration (the concept of the “Familia” [=family name], for example).

And this brings us to…

- There are a lot of Arabic loan words in Tajik.

This is something that is common to many languages spoken by Muslims. As I noted in my interview with Tomedes, it occurred to me that the usage of Arabic words in a language like Tajik very eerily paralleled the usage of Hebrew words in Yiddish. Yiddish uses a Hebrew greeting frequently (Shulem-Aleikhem! / Aleikhem Shulem!), and Tajik uses its Arabic equivalent (Salom! / Assalomu alejkum! / va alajkum assalom!).

In case you are curious as to why the “o” is used in Tajik in the Arabic-loan phrase above, this has to do with the way that these words mutated when they entered Tajik, the same way that (wait for it!) Hebrew words changed their pronunciation a bit when they entered Yiddish! (Yaakov [Jacob] becoming “Yankev”, for example)

These Arabic loan words found themselves not only in the other Persian languages but also through Central Asia and in the Indo-Aryan languages (spoken in Northern India)!

- Tajik uses pronouns to indicate possessives

Should probably clarify this with an example:

Nomi man Jared (my name is Jared)

Kitobi shumo (Your book)

Zaboni Tojiki (Tajik Language)

Man = I

Shumo = you (polite form)

This means that forming possessives because easy once you grasp the concept of Izofat.

Cue the Tajiki Language book in the picture above (on page 135, to be precise)

“Izofat is used to connect a noun to any word that modifies it except numbers, demonstratives the superlative form of adjectives and a few other words. It consists of “I” following the noun and is always written joined to the noun. It is never stressed, the stress remains on the last syllable of the noun

Kitobi nav – a new book”

Madri khub – a good man

Zani zebo – a beautiful woman

Donishjui khasta = a tired student”

(And this is the point when it occurs to you that “Tajiki”, the name used of the language by some, uses Izofat. Tajik = person, Tajiki = language or general adjective, although enough people don’t make the distinction to the degree that even Google Translate refers to the language as “Tajik”)

Thanks to Izofat, a lot of the words are not extraordinarily long (much like in English), sparing you the pains of a language like German or Finnish (much less something like Greenlandic) in which a word may require you to dissect it.

- Hearing Tajik can be an Enchanting Experience for Those Who Know Iranian Persian or Dari

Ever heard someone with a stark generational difference to you use a word you can recognize but don’t use? (for me in my 20’s, this means someone using the word “billfolds” to refer to your wallets, “marks” for your grades, etc?)

In using my Tajik with speakers of the other two Persian languages, I’ve often heard “that makes sense to me, and its correct, but it has fallen out of usage in my country”, a bit like you might be able to understand idioms of Irish English or English as spoken in many Caribbean island nations, although you might not be able to use them yourself…including some you actually legitimately don’t know!

Unlike with, let’s say, speaking Danish to a Swedish person (did that only ONCE!) and not being understood, I haven’t had problems being understood in Tajik, although I usually have to explain why I speak Tajik and not Farsi (answer: curiosity + my father didn’t get to visit there, but maybe I will! + Central Asia and the -stan countries are KEWL

I would write more about how to learn it and how to use it, but the truth is that I’m sorta still a novice at Tajik, so maybe now’s not the best time.

But hey! September is Tajikistan’s independence day, so if I progress enough by then you’ll get treated to something!

Soli nav muborak! A Happy New Year!