Many of you will have the feeling of beginning to learn a new language in which you recognize almost nothing. Vocabulary you know is scant, the grammatical patterns are different and you feel that the path of least resistance is to give up.

I highly recommend you don’t give up…because learning a language highly dissimilar to your own (whether it be your own native language[s] or ones you’ve already learned as an adult) IS possible. You will need to adjust your ways of thinking ever-so-slightly.

The good news is that you can harness various skills you have used to acquire your native language (or other languages you know) to learning your new language that seems as though it belongs on another planet.

Given that my native language is English, let’s look some of my languages in terms of “how different they are” from English on a scale of 1 to 5. 1 is very similar to English, 5 is very different. Keep in mind that this is NOT the same thing as difficulty per se.

1: English Creole Languages, Languages of Mainland Scandinavia, Spanish, German, Yiddish

2: Icelandic, Fiji Hindi

3: Hungarian, Finnish, Fijian, Hebrew, Irish

4: Kiribati / Gilbertese, Palauan, Tuvaluan, Burmese

5: Greenlandic, Lao, Khmer, Guarani

The further you get away from the West, the more likely you are to encounter languages that go up the scale. The languages in (1) are very tied to the west on multiple fronts (e.g. Atlantic Creoles, German, Scandinavian Languages and Yiddish all influencing American culture to profound degrees) the languages in (3) have all been profoundly impacted by Germanic-speaking cultures but still maintain a lot of distinctness. With that said, the English influence (add German in the case of Hungarian and Swedish in the case of Finnish) is undeniable in a language like Fijian or Hebrew (given that both were under British rule).

A friend of mine was diving into Korean and he found himself struggling to remember words. And that’s NORMAL. I had that experience with all the languages 2 and higher with the higher numbers requiring more of it.

That said, there ARE ways to remember words in languages highly different from your native tongue EVEN if it seems impossible now.

- Make Connections Between Words in the Language

Instead of looking OUTSIDE the language for connections to words you already know (as would be the standard practice in Romance or Germanic Languages if you’re a native English speaker, or even Indo-European Languages further afield), look INSIDE the language.

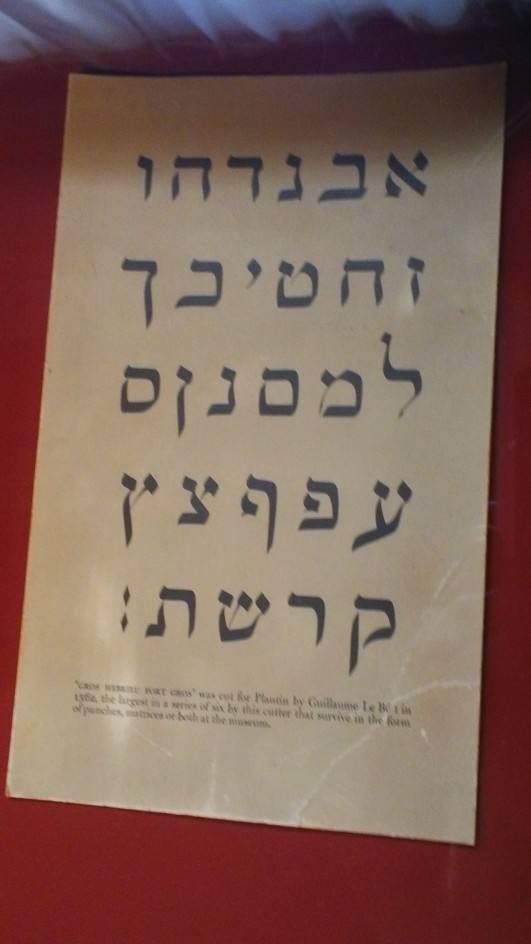

In Hebrew I encourage my students to look out for “shorashim” (or root words). These are sets of letters that will encapsulate similar meanings when seen in a sequence. Like in Arabic, the letters will dance around various prefixes, suffixes and vowel combinations that will change the meaning ever-so-slightly.

A more concrete example is with Fijian. The prefix “vaka-“ indicates “possessing the characteristics of, possessing …”. As such, you can collect additional words by looking at words with this prefix and then learning the form of the word without “vaka-“ in the front. Let’s have a look:

Wati – husband, wife, spouse

Vakawati – married (vaka + wati -> possessing a spouse)

To find words that are similar in this respect, one method you could use is to have an Anki Deck of an extensive vocabulary (what is “extensive” would depend on your short- and long-term goals with the language). Look up a root in the deck and you’ll see all words that have it:

The folks at Transparent Language have said that, minus memory techniques, you would need to see a word anywhere between five to sixteen times in order to remember it permanently. A huge advantage is that you can get exposed to one root and its derivatives very quickly in this regard.

Even with a language like English, you can do the same with a verb like “to take” which is idiomatically rich when combined with prefixes (to overtake), suffixes (to take over) or direct objects (to take a break).

Out of all of the languages I have learned, the same principle holds and can be taken advantage of.

- Do the Words and Expressions You Want to Learn Tell Any Stories?

Let’s take the Lao phrase ຂໍ ໂທດ (khɔ̌ɔ thòot). It would mean “I’m sorry” but it literally means “request punishment”.

Various languages don’t have a very “to have”, instead they would say something like “there is upon me” (Finnish) “there is by me” (Russian), “there is to me” (Hebrew, although Hungarian also does something similar sometimes) or “there is my X” (where X is a noun – Fijian, Kiribati / Gilbertese and Hungarian do this)

Arcane sentence structure can actually be an ADVANTAGE in some respects. Greenlandic’s mega-long words can be a great conversation starter AND something for you to remember.

Words, phrases and idioms tell stories in your native language too, but chances are you probably won’t be aware of them and if you do eventually, it may be after a decade or two of speaking it, if not more.

- Associate Various Words with Entertainment or Things that Have Happened in Your Life

Scene: a synagogue event.

I got “Colloquial Hungarian” earlier that day. I met a Hungarian girl and the only thing I know is a basic greeting. I ask how to say “pleased to meet you” and she says “örülök hogy megismertelek”. You can imagine how much I struggled with this simple sentence on day one, much to her laughter and those looking on.

The fact is, I never forgot the phrase since. Because I associated it with that incident.

You can also do the same with individual words and phrases that you may have heard through songs, song titles, particularly emphatic scenes in movies, books or anything else you consume for entertainment in your target language.

The over-dramatic style of anime actually helped me learn a significant amount of Finnish phrases as a result of “attaching” them to various mental pictures. Lao cinema also did something similar. Pay attention ever-so-slightly to the texture of the voice and any other details—these will serve as “memory anchors”. It’s a bit like saving a GIF to your brain, almost.

- Hidden Loan Words from Colonial Languages.

The Fijian word for a sketch / painting is “droini”. Do you see the English cognate?

It’s the word “drawing” –Fijianized.

Do be aware, though: some English loan words can mutate beyond their English equivalents in terms of meaning. Japanese is probably infamous for this (in which a lot of English loan words developed lives and meanings of their own, much like Hebrew loan words in Yiddish sometimes found themselves detached from their original meanings in Hebrew).

Another example: Sanskrit and Pali words in languages of Southeast Asia in which Theravada Buddhism is practiced. Back to Lao. The word ປະເທດ (pa-thèet) may be foreign to you as the word “country”, but you’ve probably heard the word “Pradesh” before in various areas of India, even if you know nothing about India too deeply (yes, it is the same word modified for Lao pronunciation). The second syllable in particular may be familiar to you as the “-desh” from “Bangladesh”.

Which brings me into another point…

- Do You Recognize any Words through Proper Nouns?

Tuvalu is a country in the South Pacific. It means “there are eight”. The Fijian word for to stand permanently or to be built is “tu” and the word for eight is “walu”. Fijian and Tuvaluan are not the same language but they are family members. You can recognize various other words by determining what place names mean or even names of people you know (whether well-known historical characters or your personal friends).

Another example: Vanuatu. Vanua in Fijian is a country or a place. Tu is the SAME root that we have in “Tuvalu” (yes, the “tu” in “Tuvalu” and “Vanuatu” mean THE EXACT SAME THING!) Vanuatu roughly means “here is our country” (or “country here”)

Again, this is something you can do for many languages. I remember doing in in Germany as well.

Lastly…

- Embrace the Differences in the Grammar

I was amused by the fact that the Tuvaluan word for “to understand” is “malamalama”. I posted it in a small polyglot group. A friend of mine who studies mostly languages from Western Europe and the Middle East asked me to conjugate it.

Tuvaluan doesn’t have verb conjugation. It instead puts particles before a verb to indicate tense. “Au e malamalama” -> I understand -> I present-marker understand.

Surprisingly this system (not entirely foreign to me because of having studied other languages in that family) was not foreign to me. But I learned to like it. A lot.

Feel free to tell interested friends about what makes your different language very different in terms of grammar. Some may even be intrigued about the fact that many languages don’t have an equivalent of “to have”.

There are some things that are a bit difficult to embrace, such as Greenland’s verb conjugation that has transitive forms for each pair (in normal English, this would me an I X you form, an I X him / her / it form, an I X all of you form, an I X them form, a you X me form, a you X him / her / it form … FOR EVERY PAIR).

That said, your love of your new language will find a way.

I’m sure of it!